Exhibition Text

*

I made

my decision this morning—soon after eight o’clock, as I stood by the

front door, ready to drive to the office. All in all, I’m certain that I had no

other choice. Yet, given that this is the most important decision of my life,

it seems strange that nothing has changed. I expected the walls to tremble, at

the very least a very subtle shift in the perspectives of these familiar rooms.

—

J.G. Ballard, The Enormous Space,

1989

*

Oh, I’ve seen that already.

— What’s so wrong with art being

familiar?

2016. I had

planned a different text. I had

hoped—having woken up on the morning of June 24th, to find

that the UK had not voted to leave the EU—to have restaged familiarity as

something else than the building of distinctions between the unfamiliar and

unknown. As something which could be generative and abundant, rather than

conservative and divisive. It had been intended to ask why artists untethered from the cannon, but nevertheless tied to an

never-ending cycle of innovation could not make things that might be vaguely familiar:

whether by relation to an art history that won’t go away, or out of an affinity

that they draw from their peers, or, in an age of Internet communities of

association and referentiality, an affinity they might

want to draw.

But on the morning after the

referendum, this idea seemed pretty thin. How can it be possible to argue for

familiarity and recognition, when it has been so forcefully and so effectively

mobilised by a campaign founded in hate and xenophobia against its political opposite,

the other, the unfamiliar, the migrant? A persistent vision of the familiar that

multiplied structural separations, sliced down geography and generation, and

which wasn’t going to go away.

Not only has the familiar become

so etymologically radicalised into an obessives version

of a family footing that it only refers

to an ethno-nationalism: but the fifty-fifty split between those who identify

with, and those who identify against looking outwards for their sense of

familiarity also defines how strictly that border between what is known or not

has become. It’s a border that art, and its perpetual building of autonomous

archipelagos against the familiar, mundane and everyday has

long participated in.

1790. Art’s

stubborn obsession since Kant’s Critique

of Judgement with autonomising itself from the daily conditions and

structures it nevertheless sees as its task to speak of, for, and to—places

the familiar and everyday as both the most desirable setting of participation for

art, and a condition of being that must be avoided at all costs.[i]

This, even as the lessons of institutional critique—that art institutions

and its varied histories are fully enmeshed and reproductive of the structural

reality that corrals the lives of “everyday” people—take full effect on

how autonomy is understood. In the innovation and individuality-obsession of

the marketized art world that takes the institution’s

place (still coupled with the fascinated aversion to “the real” of autonomy)

now sits the worst possible, but also most likely and knowing, accusation to be levelled at an artwork:

—

oh that reminds me of … yeah I’ve seen it

already.

What is in that pressure to

invent and re-invent? With predictable regularity, art and artists are tasked

only to take the familiar into the unfamiliar—to effect on the norm an

irrevocable change on what is commonly known, rendering it particular,

subjective, surprising, autonomous from familiarity—to draw a line

between itself and what could come to be familiar?

Of course the autonomy of the de-familiarized

isn’t without a history of good intentions. Even autonomy, whose principles

were laid out by Kant, Hegel, Diderot, etc., as they began the modern project,

aimed to carve out a social space for art away from the utilitarian rationality

of the general economy in nineteenth-century Europe in order that it could develop

“audacious, scandalous, seditious works and ideas.” 1917/19. Elsewhere and later on, in his essay The Uncanny (1919), das unheimlich, Freud took this task a step further, and

pointed to a simultaneous familiarity and foreignness: a jarring discomfort in

the individual experiencing it that underwrote the work of artists ranging from

the Surrealists to Sarah Lucas to Mike Kelly. Then in 1917, Russian writer

Viktor Shklovsky coined the more collective term ostrananie. Translating

as either defamiliarisation or estrangment,

the term argued for art (or poetics) to revitalize that which

had become clichéd or overly familiar,[ii]

and giving rise to any number of truth-saying artworks.

But while this strategy of

unseating the stasis of the status quo might

have been at one point about drawing attention to the potentiality of artistic

language as a contrast to the familiar and functional. A collapsing of the

boundaries between the familiar and the unfamiliar has also been more

importantly and recently deployed as a politics against cultural construction

itself, (which in the art of autonomy had never strayed very far from

parameters set by a modernity grounded in western liberalism). For postcolonial,

feminist, posthuman and queer theory it is precisely

this terrain of both the familiar (or neutral which must be challenged—a

position granted to the white western male to and by itself and which others every indigenous, femme, queer,

trans, black person, person of colour, plant and animal perceived to exist outside

of this (and their) status—but also as Egbert Alejandro Martina[iii]

writes, the assumption that it is a desirable future for the “unfamiliar” to be

assimilated into what is defined “the norm,” with all of the expectation its

etymological burden intact. As in decoloniality, not

only does this mean repatriation of what is taken in an actual sense, but also of

the right to form those definitions outside of western traditions.

Simply undermining defamiliarisation, askingwhat is

wrong with something being familiar would then miss the point. The challenge to

the power of the familiar as a social-structure is different to the expectation

on artist to defamiliarise the “normal”—as well

as artist’s increasing reaction to this, but they’re not unconnected. Instead

it could be better to ask why this distinction keeps being reproduced as it

does, why what is put into the realm of the unfamiliar is kept there, and what

art has to do with this.

*

2016/2012/ 1978. The

clash between generations and geographies in the 2016 referendum could be said

to be one between the history of territory and future of circulation. As Angela

Mitropoulos has argued, following Michel Foucault’s depiction in his 1978 CollŹge de France lectures of the shift in sovereign power

lying in containing territory to policing (securitising) movement through

and among that territory[iv] (derivatives

vs. gold reserves, free moment of labour vs. a job-for-life and so on): far

from a theoretical distinction, this policing has become a deeply and

intimately political one.[v] To

participate as citizens in this setting, not only must we control “good” circulation—watching

our weight, as much as becoming more digital, etc.,—but

we must control against contagion, or the “bad” circulation that might infect and

upset the circulation of norm. Not doing so would threaten the health of the

national body. As Mitropoulos points at protecting that norm at every level of

intimacy is the new contract between the individual and the state.

2016. But whether

its debt, health-choices, or free movement, we’re not exactly all in this

together. To control that movement we need borders and definitions. Deviations

from the perceived norm, from that border of the nationally-familiar

(raced, of sexuality or gender, political, or ideological, etc.,), become a threat

against the familiarity of the nation that must not pass. And if, as Frances Stonor Saunders writes in the London Review of Books

“cognitive mapping is the way we mobilise a definition of who we are, and

borders are the way we protect this definition,”[vi]

then a hold on the autonomy of mapping, on the privilege of being separate from

the flow, and participating in the mapping and delineation of good/bad

circulation can, simply put, only ever continue to multiply these borders[vii]

rather than do away with them altogether.

*

1989. In an

act of self-aggrandizing little-islander separatism, the main character In J.G.

Ballard’s The Enormous Space decides

without much forethought to shut the front door on the excessive banality of

the world out there. He leaves behind

work and ended relationships, and buries himself into the controlled familiarity

of his suburban Croydon home. Shutting out the

familiarity of his past life with the ultra-familiar closed box. Privatising

it. He becomes smaller and smaller as the inside of the house engulfs him:

“No

longer dependent on myself. . . . I am free to think

only of the essential elements of existence—the visual continuum around

me, and the play of air and light. . . The house

relaxes its protective hold on me . . . A curious discovery—the rooms are larger. . . .

My eyes now see everything as it is, uncluttered by the paraphernalia of

conventional life. . . . The true

dimensions of this house may be exhilarating to perceive, but from now on I

will sleep downstairs. Time and space are not necessarily on my side.

He spends longer and longer in the

seclusion of the rich, deep interiority of the house that has driven him to both

madness and morbidity. “Three months—. . . The

house enlarges itself around me . . . The walls of this once tiny space

constitute a universe of their own . . . So much space has receded from me that

I must be close to the irreducible core.” He lies next to his dead secretary in

the freezer, “the perspective lines flow from me, enlarging the interior of the

compartment. Soon I will lie beside her, in a palace of ice that will

crystallise around us finding at last the still centre of the world which came

to claim me.” The further he withdraws the clearer the paradox, everything that

encases him expands and grows more voluminous the more he becomes familiar with

it. It is only the ensuing madness of starvation and solitude that can keep him

separated from this familiarity which comes to claim

him.

*

2013. Writing

on the emerging political subjectivity of usership that

he argues has come with the rise of user generated content, web 2.0 culture, and

widely available political and economic instruments, writer Stephen Wright

describes how the user exerts their agency “paradoxically, exactly where it is

expected.” They do this against the “conceptual institutions” of

“spectatorship, expert culture, and ownership,”[viii]

that make up a contemporary culture still based on the idea that art can and

should be separated from its use. Wright pitches usership

as something operative in the hear-and-now rather than as something waiting for

a revolutionary moment to transcend it. Usership is “all

about repurposing available ways and means without seeking to possess them,”[ix]

For the expert use is always mis-use. But at the same

time usership is never ownership. Like this, usership is unlike participation, which plays by the rules,

but instead like a sort of self-regulating, hands-on, thing. Its terms are made

in the agreement, and in proximity.

Though he had a figure, its

sphere of engagement remained illusive. And even though Henri Lefebvre and

Michel de Certeau had persuasively analysed “the

goings-on, inventiveness and usership of what has

come to be called ‘the everyday’,”[x] this “wasn’t

quite right.” Perhaps it was too universal for what he hand in mind. In any

case it came, overheard in a bar one day. “A regular stepped up to the bar,

exchanged a quick glance with the barman who asked, invitingly, as if confident

in what he already knew, ‘the usual”?”[xi]

It was not was expected, but what had come to be agreed through use. The usual

is not easily familiar, but particular and subject to change. “Operative only

in the here and now.”[xii] It is in

this sense that Wright can claim that if art can be used rather than the

subject of expertise, then its sphere of engagement will support equally

particular and changeable Artworlds or

“art-sustaining environments.” Artworlds whose use make the one-world of Art’s autonomy drastically

unstable.

*

2016. The

usual comes through the shared use of the usual and not through its inheritance.

The autonomy of art has done a lot to create one, single, art world with itself

as the norm. A norm that only wants the new and the familiarity

of the unexpected. Using art,

on the other hand it is said creates many art-sustaining worlds, many worlds

that support much more than just art. I write this because the artists here share,

if not something in common, an affinity, something familiar between each of

their works. They want it. Let’s be clear, familiarity is used as a tool to boil

political identification down to the lowliest common denominator, the body as a

border to be protected or prosecuted against. But if a search for affinity and

reference recognizes the radical abundance of becoming familiar—rather than policing the norm by

controlling the opposite—then perhaps we could say, artists using familiarity, pluralizing and

agreeing on it, joining what they are making with the world they are in, undo some

of the borders produced by obsession of art to be autonomous and apart.

Refugees are welcome here, as are

migrants, as are those already here, as are all those disaffected by the

structural inequality of a country for the few: not because they threaten the

familiar, but because they expand it. Because they un-police

its borders. “We construct borders, literally and figuratively, to

fortify our sense of who we are,” but “we cross them in search of who we might

become.”[xiii]

Being able to say this looks like something

that might become familiar is one way to begin that crossing.

— That looks like …

— The usual?

— Sure.

x

TC

2016

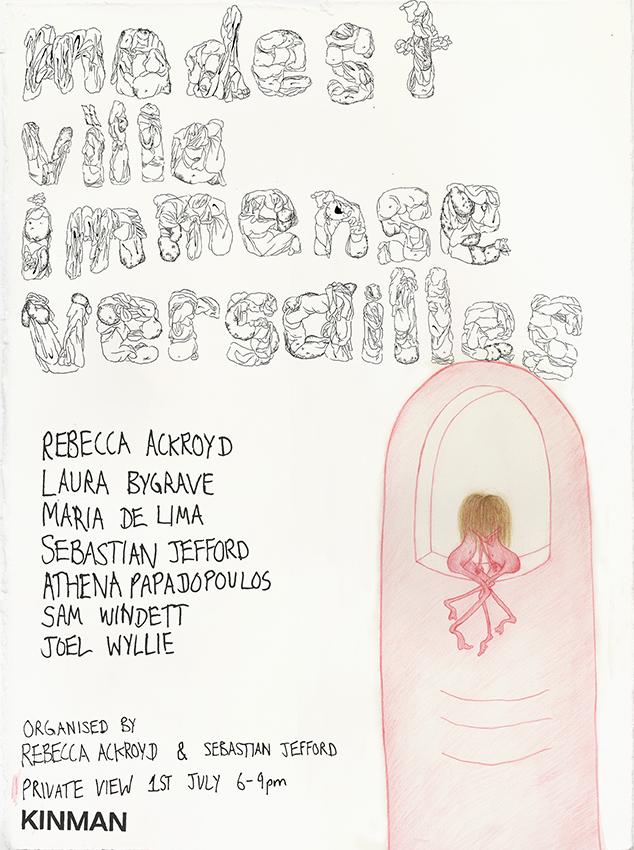

This text was written on the occasion of the exhibition "Modest villa immense Versailles," Kinman Gallery, July 2016. Featuring Rebecca Ackroyd, Laura Bygrave, Maria De Lima, Sebastian Jefford, Athena Papadopoulos, Sam Windett, & Joel Wyllie.

[i]

This paradoxical relationship between the disinterested spectatorship of that

which art speaks and looks (precisely the everyday the art world is separated

from) and the purposeless purpose (its function, what it does, without being

useful or valued like other objects or things are), which is at the core of

Kant’s attribution to art of an aesthetic function, polices the boundaries of

art’s autonomy as a trinity of use-less objects, non-subjective disinterested

spectatorship, and the agency of the possessive individual. This in spite of the consequences, that the

institution art still ultimately for the most part sits on the sidelines in the

false totality of the art world, a unitary world set apart.

In short this relationship is what keeps the familiar at bay until it is

brought into art, and universalizes rather than particularizes the conditions

into which the everyday is dragged. It all just becomes just Art.

[ii]

Viktor Shklovsky, "Art as Technique," 1917.

[iii]

Egbert Alejandro Martina, “Thinking Care” processed

lives, 9 Novemeber 2015, online at: https://processedlives.wordpress.com/2015/11/09/thinking-care/

[iv]

Michel Foucault, Security Territory,

Population (Plagrave Macmillan, 2007)

[v]

Angela Mitropoulos, Contract and

Contagion (Minorcompositions, 2012)

[vi]

Frances Stonor Saunders, “Where on Earth are you?” London Review of Books,

Vol. 38 No. 5, (March 2016) online at:

http://www.lrb.co.uk/v38/n05/frances-stonorsaunders/where-on-earth-are-you

[vii]

See: Brett Neilsen and Sandro

Mezzadra “Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of

Labour,” Transversal,

No.3 (2008) online at: http://eipcp.net/transversal/0608/mezzadraneilson/en and

Sandro Mezzadra, “living in

Transition,” Transversal, No. 6,

(2007) online at: http://eipcp.net/transversal/1107/mezzadra/en

[viii]

Stephen Wright, Towards a Lexicon of Usership, (Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum,

2013) p. 66.

[ix]

Ibid. p. 68.

[x]

Ibid. p. 65.

[xi]

Ibid.

[xii]

Ibid. p. 66.

[xiii]

Stonor Saunders, Ibid.